When I consider how my Korsakow films have been received, it seems to me that the subjects I1 have dealt with – the “stories I have told” – are rather secondary.

Books (and many texts) have been written about Korsakow. Although individual works, such as [The LoveStoryProject], have been repeatedly discussed (as in Sandra Gaudenzi’s PhD), the “actual” content of the works has rarely been at issue.

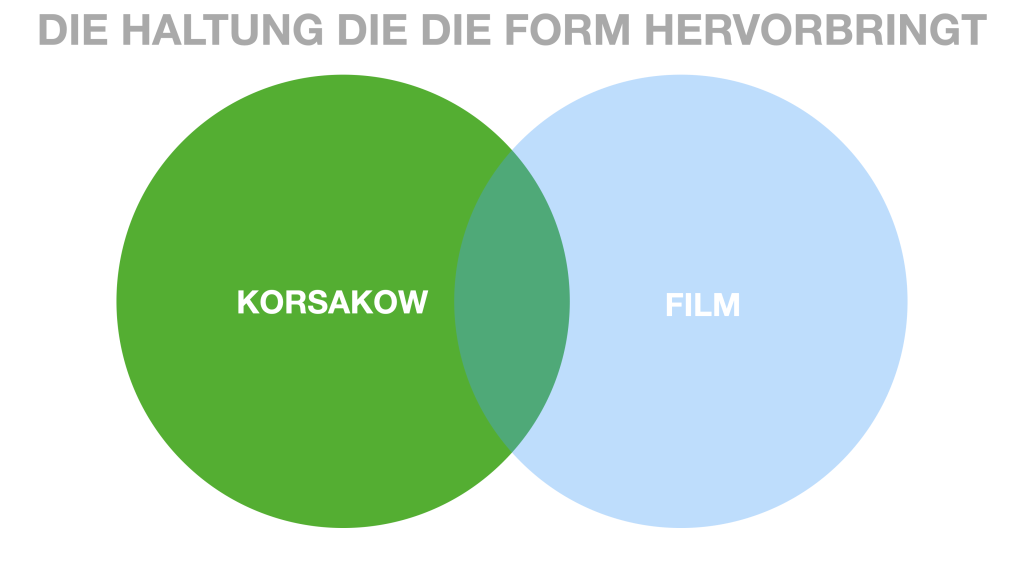

What seems to be unusual, and has been and is being discussed, is the form – the form in which certain Korsakow films are made, expressing an attitude (Haltung) not seemingly so evident in other forms of cinematic storytelling. It is, then, this form that seems to produce an attitude, at least in authors who engage with it. Not all authors who use Korsakow arrive equally at this attitude; many authors, according to my observation, “resist” the form; it seems to me that they work against the form, or as I put it earlier, brush Korsakow against the grain.

From my point of view, such projects fail and Adrian Miles also describes this when he talks about how many people don’t get Korsakow properly. I recommend to these people to use more linear formats and to avoid misunderstandings I would like to say here that this is also completely o.k. from my point of view. The attitude Korsakow affords is not “the right one” it is just a different one. In my opinion, both attitudes have advantages and disadvantages.

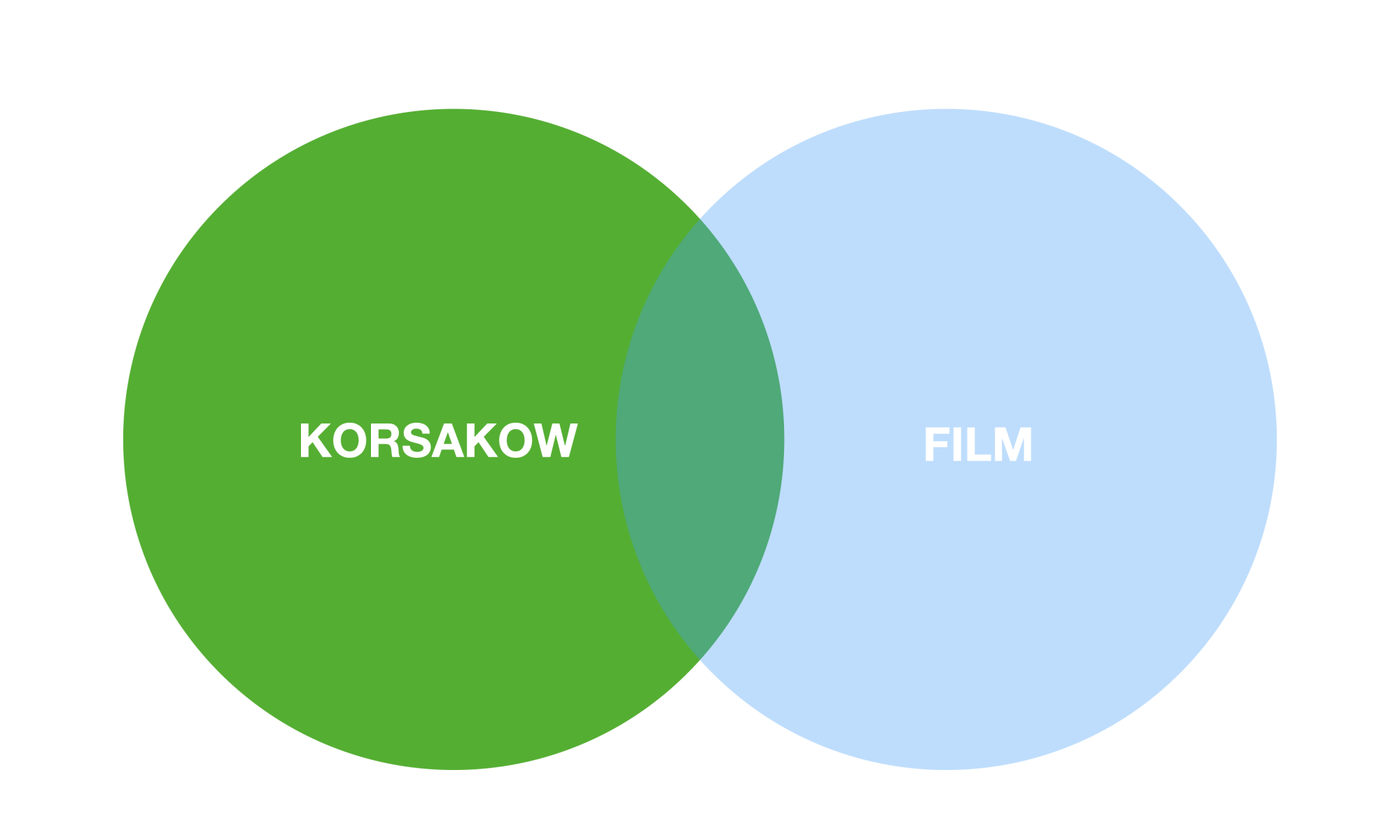

The form seems to be – at least with Korsakow – an essential content and I wonder if this is not true for other kinds of projects as well. Whether, for example, the themes of linear films are perhaps not as important as generally assumed, whether perhaps the form in which linear films are told has a greater influence on the thinking of those who make the film and those who receive the film. I deliberately choose the grammatical singular (“linear film”) here, although I am aware that there are many forms of linear film that can produce a wide range of different attitudes. My argument is that linear film has a range of possible attitudes, as does Korsakow, some of which overlap but some of which do not.

This part that does not overlap would be the part that afforded an attitude that linear film does not. This area interests me – fervently.

Because the attitude seems to me to form the view that one can take on something.

1 and authors with whom I collaborated