Questions by Gülden Tümer

Gülden Tümer has been working as a journalist for more than 10 years. Currently she is doing her master degree at Radio, TV and Cinema Department at Faculty of Communication, İstanbul University.

GÜLDEN TÜMER: According to Ersan Ocak, “In cinema, explorations and experiments on the forms of representation have been made mostly by documentary and experimental filmmakers” (2012: 959). Here, I want to ask why have documentary filmmakers always sought new forms of representation?

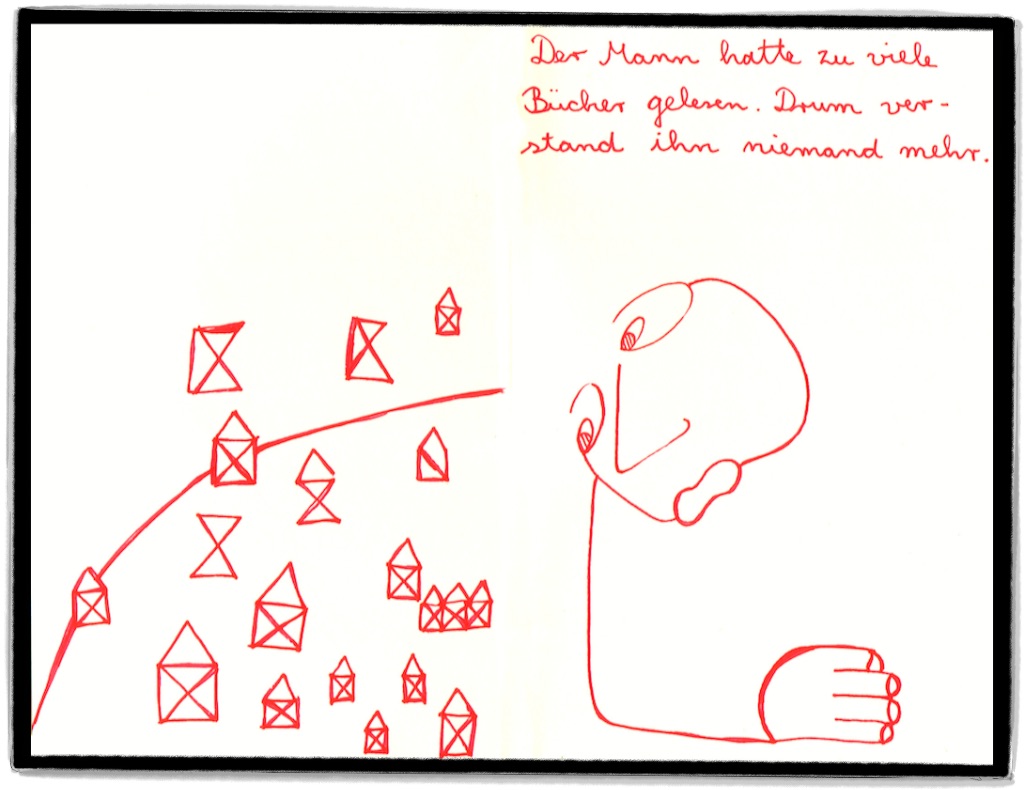

FLORIAN THALHOFER: Not so sure if documentary film makers in general have always been so inventive. I guess most documentary film makers work within the boundaries of the craft of making films and are perfectly happy with the medium of linear film. But some filmmakers felt the concrete walls of linear narration and tried to explore alternatives. In my case I have not been a filmmaker, I started with exploring the possibilities of computer to improve communication between humans using images, audio and film.

So why do documentary filmmakers

So why do filmmakers

So why do humans always sought new forms of representation?

Well, I guess the answer is simply because the forms of representation, that are available, are not satisfying (never have been and most likely never will be). All forms of representation, all forms of communicating, sharing thoughts, views, ideas are less than ideal. So some humans search for better ways to communicate, to find better ways to represent bits and pieces of the world.

Most people just follow the rules, communicate the way they were told by the elders, and if they hit the concrete wall, they ignore it.

GÜLDEN TÜMER: “New media documentary transforms the cultural form of watching a film. The audience engages with new media documentary by navigating. Why do people prefer to be “user” within a documentary film rather than solely sustaining the joyful state of just sitting and watching a film?” (Ocak, 2014: 256). What would be your response to this question for a Korsakow-film?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: Watching a Korsakow-film and watching a linear film are two very different things. Like reading a book and listening to a podcast. It is not that nonlinear films will replace linear films. Nonlinear film just seems to be something that is relatively new. There were experiments with nonlinear films conducted in pre-computer times, but of course computer facilitate the creation of non-linear films much better, and to create rule-based nonlinear films (such as Korsakow films) without a computer is almost impossible.

So what is the motivation for someone to view a Korsakow film?

People who prefer to use their own brain to make sense of a particular topic will prefer a Korsakow film. That way a viewer can explore and get a sense of the many angles to a topic.

(own brain / many angles / complex reality)

What is the motivation for someone to view a linear film?

Someone (usually the film-maker) thought a long time about a topic and presents the viewer with one or a very limited number of angles to understand it. This is very convenient for most people. So viewers do not have to spend so much energy or brain power – the thoughts are thought already and prepared for them.

(author’s brain / limited angles / simplified reality)

Also, almost all living humans were conditioned from early age to enjoy linear films. Kids grow up with linear films and learn to read, understand and enjoy it.

But nevertheless some people have a hard time accepting other people’s thoughts. Some people really enjoy to think for themselves. But at the moment we have not so many tools that facilitate that. Korsakow is such a tool.

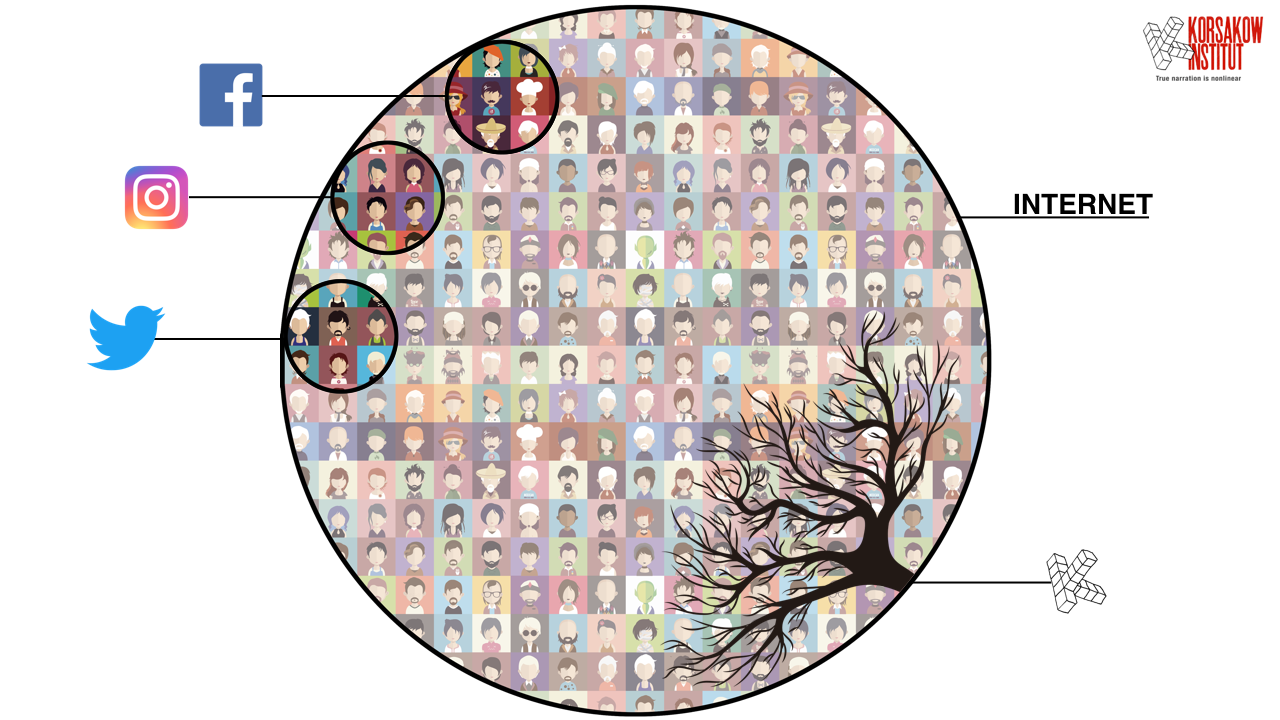

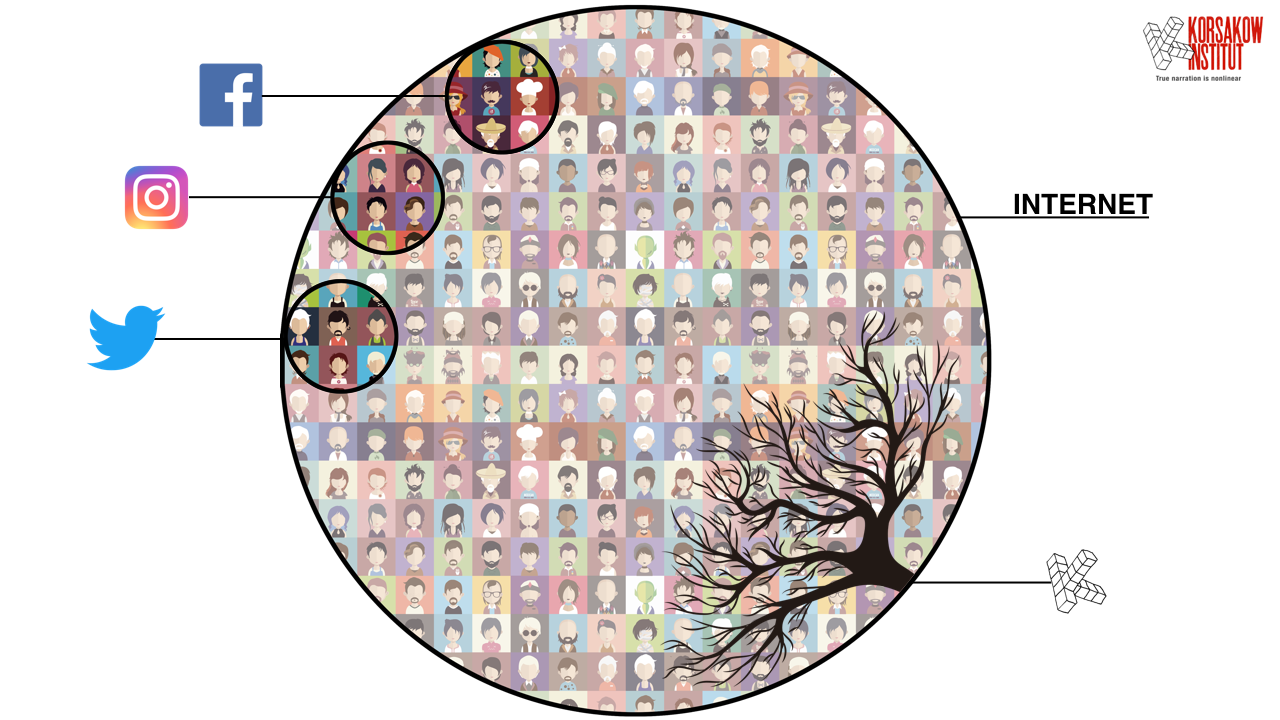

For people who are interested in reality, linear film is in fact not such a great tool. I like to say: there is no such thing as a documentary film. Every linear film is fiction. Linearity does not exist in reality.

GÜLDEN TÜRER: On the other hand why do people still prefer just watching a fiction film? Or do you think it will change too?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: I guess people will always be interested in watching linear fiction films. It seems somehow relaxing to be presented with a fixed and never changing angle on the world.

GÜLDEN TÜRER: You said that people doesn’t think in a linearity so storytelling must be in change. What are the advantages and disadvantages of non-linear storytelling?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: Stories have the advantage that they make things easily understandable. But at the same time they have the disadvantage that they are almost always wrong (or at least that they are far from being accurate).

Nonlinear narration is not true, neither, but it is closer to reality. And that we are closer to reality, when we are thinking trough and discussing the problems we currently face (like nuklear extinction, climate change), is probably the key factor when it comes to finding solutions that allow our survival.

GÜLDEN TÜRER: “In a new media documentary, the user can establish his/her own sequence flow and, in a sense, makes a non-linear editing of the project” (Ocak, 2012: 963). But we know that in this era, we all surf on the internet. And it causes distraction. In spite of this distraction problem, can the audience complete all parts of documentary or not?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: Distraction has a very negative connotation. But maybe distraction is not a bad thing. Especially in times of information overload.

Imagine a thirsty monkey, who gets to a lake. The monkey drinks. When the monkey had enough the monkey stops drinking. Does the monkey get distracted from drinking? Sure. Something else crosses the monkey’s mind and the monkey stops drinking and does something else. If the monkey would stay focussed on drinking, the monkey would drown.

An aware mind that changes the focus of attention is still attentive. And that is a good thing.

Human monkeys, that focus – for example – on propaganda stories and don’t get distracted, are in a worse situation than those, that feel like they had enough and focus elsewhere.

It might be easy to stay focused when watching a seductive, exciting linear film, but the whole film, the whole experience is a distraction.

GÜLDEN TÜRER: We can say that in new media documentaries, which are established on databases, “each and every shot has equal significance, each and every story has equal significance” (Ocak, 2012: 963). Here I want to ask that if a user without completing one part, start to watch another one because of surfing habit, can she/he understand whole story?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: I think there are different approaches in new media documentaries and different authors have different approaches. The way I use Korsakow (and again there are other approaches) – I can see that you think that every SNU has equal significance. I never looked at it that way. Interesting observation!

In a linear film – because of its fixed sequence – one scene builds on the previous scene, the scenes build up. In that sense, some scenes are elevated. Only in a system like Korsakow you can achieve to have scenes on an equal level. And usually I try to have it like this.

If the author wants to deliver a message, the viewer has to get the whole (or if not the whole then most of the) story. But I don’t want to deliver a message. There are things to learn, actually there are many potential messages, but the message is born in the viewer’s brain, not in mine.

Once, when I presented my first Korsakow film [Das Korsakow Syndrom], I was asked: And what is the message of the film? – I did not have an answer then, but I have it now, after thinking about it for many years: The film is the message. If I had a message, I would have writen it down in a sentence. Writing down a sentence is far less effort than making a film.

GÜLDEN TÜRER: “Today we can easily see that, play is everywhere in the new media environment” (Ocak, 2014: 258). Audience is not just a user within documentary film, she/he also becomes a player as a homo-ludens. Do you think it can prevent distraction?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: From the reactions I often observe when people watch Korsakow films, they seem to experience it more as work, than play.

😉

Anyway, even from early age on, I never understood what the difference between play and work is. Now I would say both is an exercise – an exercise to shape the form of the connections in our brains. You create paths of thinking in your brain when watching a blockbuster Hollywood film or when watching a Korsakow film. You train your thinking.

To my understanding: watching a blockbuster Hollywood is harmful for your thinking, whereas Korsakow is a good exercise!

GÜLDEN TÜRER: I watched your Planet Galata, and I like it too much. Why you make some changes on it?

FLORIAN THALHOFER: Thank you – happy you like it! Planet Galata was originally made with Korsakow Version 5. I recently updated it to Korsakow 6. Korsakow 6 has a number of new possibilities. I was playing around with it.

A Korsakow film is never fixed!

Ocak, E. (2012). New Forms of Documentary-Filmmaking within New Media. AVANCA|CINEMA 2012, International Conference (2012). (959-965)

Ocak, E. (2014). New Media Documentary: Playing with Documentary Film within the Database Logic and Culture. In D. Moser and S. Dun (Ed.), Digital Janus: Looking Forward, Looking .Back (255-262). Oxford, United Kingdom: Inter-Disciplinary Press.