The New York Times April 18, 2020

That’s the kind of story the news likes to tell. It’s a great story because it’s unusual and disturbing at the same time.

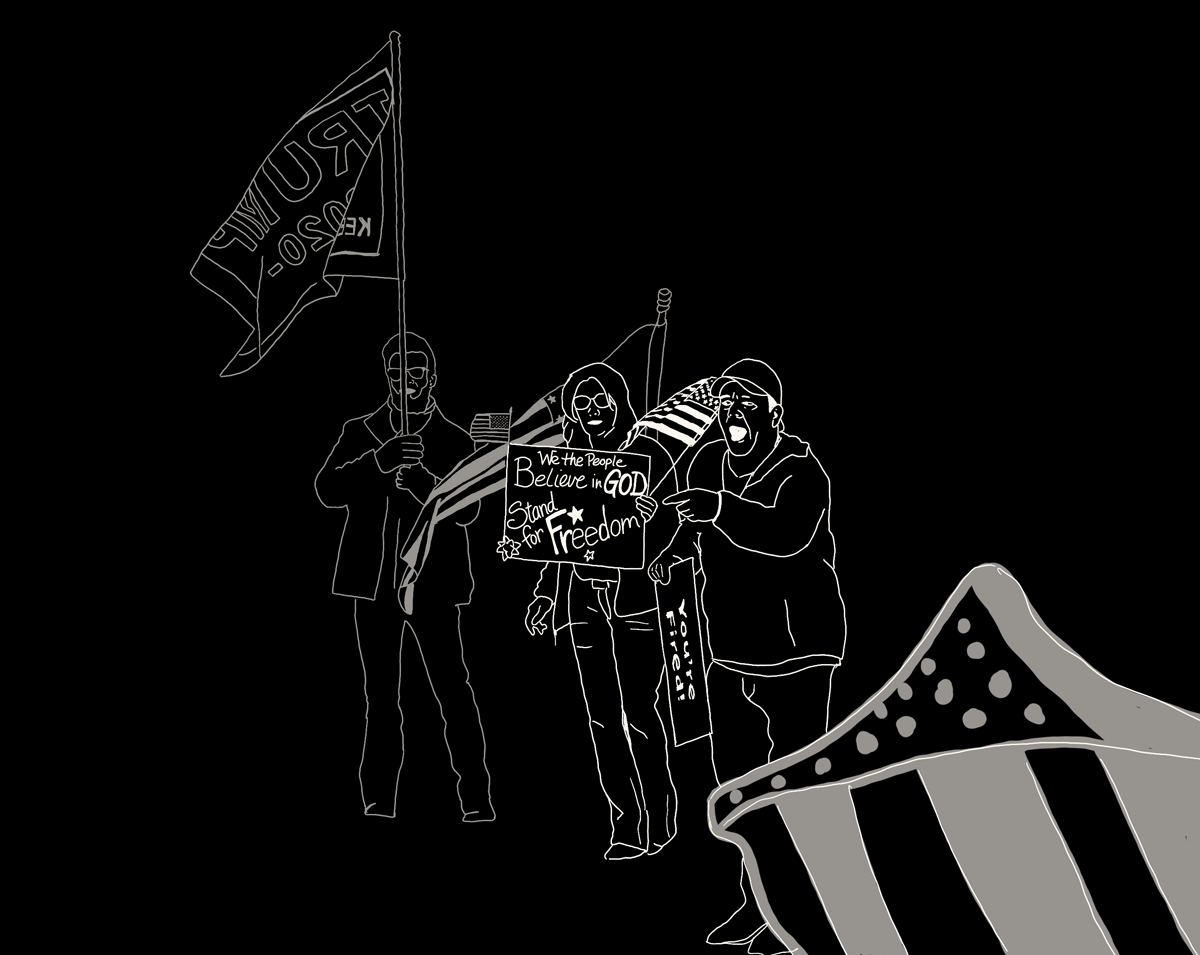

Unusual because we should all have understood by now what this virus is all about and why and how we should help to contain its spread. Disturbing, because there are people who see it differently, express it militantly and thus again become a danger to everyone.

Somewhere in the USA, where not only the brightest lights live, hundreds (and on the pictures it looks more like hundred than hundreds) of the most stupid apes have gathered, waving blue-white-red flags and doing hullabaloo. They protest that the lockdown will be lifted. They demand their normal life back.

This is stupid for two obvious reasons.

1. as long as a larger part of society is afraid of a contagious disease, which can best be protected from by renouncing normal life, there will be no normal life.

2. it is a stupid idea to form a group with 100 others at times when a contagious virus is circulating.

In the sense of the opponents of the lockdown, an information campaign would make more sense, which explains to the people that their worries are completely unfounded because… And exactly this “because” is what is lacking. Because there are no good arguments. (The “argument” of the lockdown plunges many people into a shitty situation is not an argument, it is an observation).

Putting yourself in a group of 100 people at the moment is also pretty stupid, because it increases the risk of getting infected with the virus (even if you don’t believe in it). But this demonstration is unlikely to result in its participants becoming infected. The larger the group of people, the more likely they are to be infected, but for this relatively small group, the probability is not too high.

So most likely these idiots will not be infected, but they will probably use this as a way to “prove” how exaggerated the fear is. (Strictly speaking, they are just proving how bad their understanding of probability is, but that is nothing unusual, because humans in general are terribly bad at grasping probabilities intuitively (see Kahneman, “Thinking, Fast and Slow”).

The danger is high, however, that they will give others stupid ideas.

The perfidious thing about the story of the events, like the demonstration of the stupid monkeys in Minnesota, is that telling the story leads to many more people getting similarly stupid ideas. If 1000 times 100 people meet and wave flags, then we will almost certainly have a Super Spreader Event. That will actually have an impact.

So the only really scary element in the story of the demonstration of the stupid monkeys is the fact that we tell it to each other – and spread it by telling it.

In fact, the story is like the Corona virus itself. Anyone who tells the story transmits the virus. Most people don’t get sick.If someone gets sick, one symptom of the illness is that they go out into the street, form groups with others, wave flags and shout “Freedom!

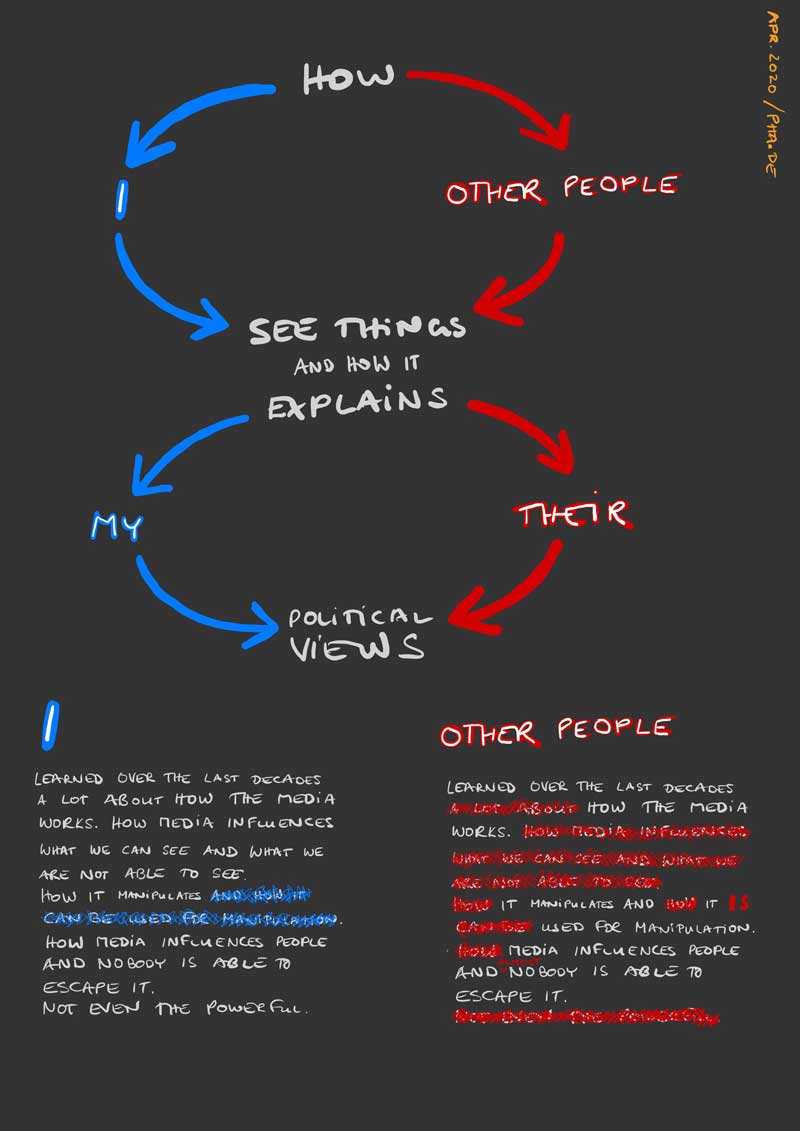

By the way, this is the same with all stories. (The symptoms of the respective illness are very different and in most cases completely harmless).

Stories are viruses.