And why this title is wrong

This is the paper I submitted alongside a video that can be viewed on YouTube.

Abstract

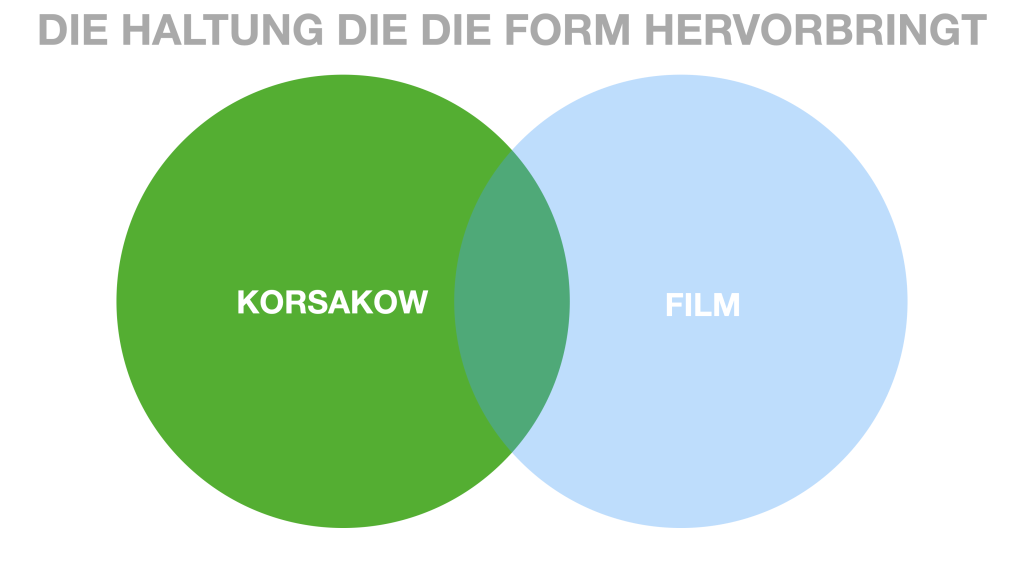

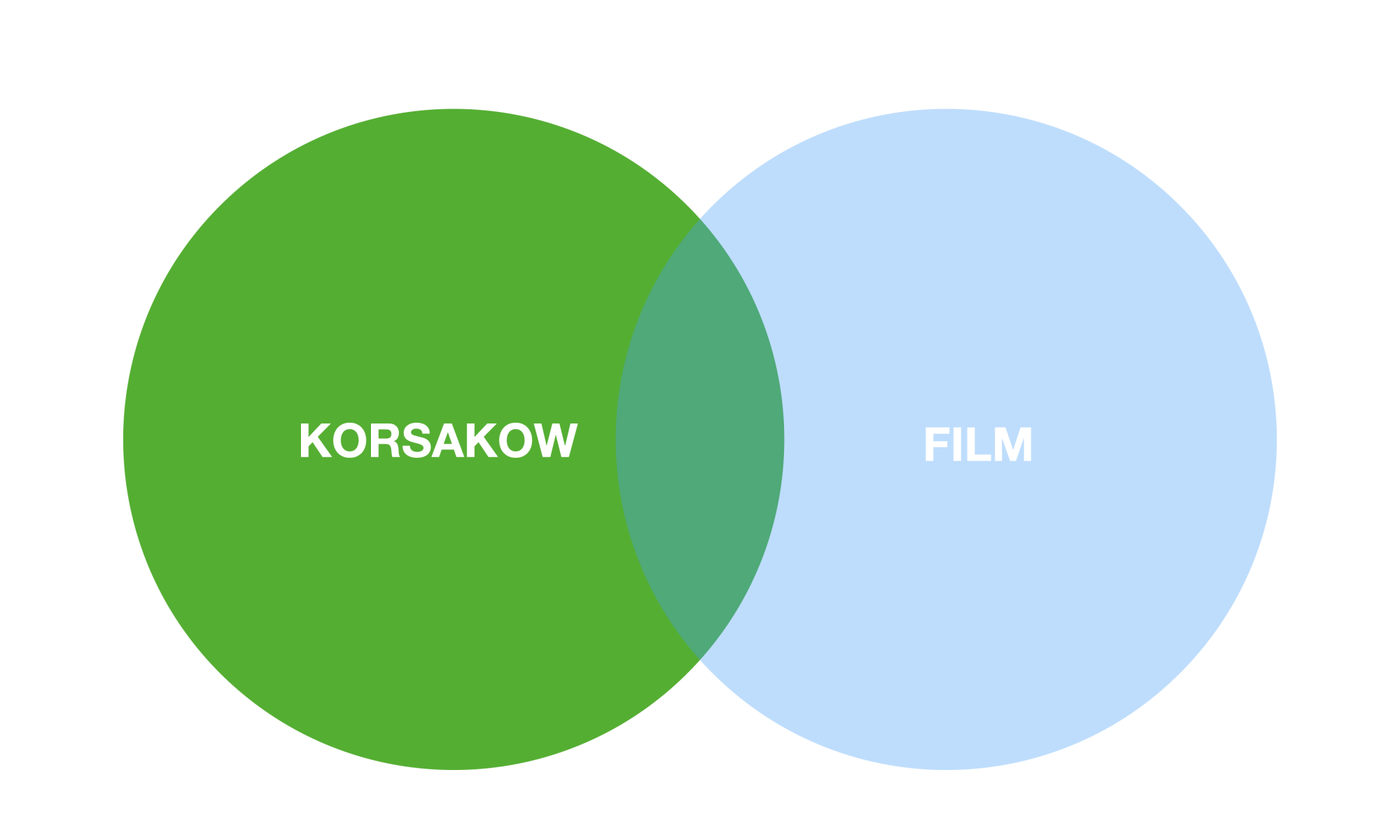

The thesis with which I started my PhD, and which is also reflected in the title of this talk, is that my particular way of working with korsakow – which I call korsakowian – has shaped my thinking in a way for which I have been using the term “multi-perspectival” since 2012. My auto-ethnographic explorations now point to that it is the other way around. Media that affords a korsakowian approach attracts people with a certain kind of mindset, that I would like to call multi-perspectival.

Keywords

multiperspectivity, media-literacy, Korsakow, korsakowian

1. Introduction

Six months ago I submitted an abstract to IFM with the title “The korsakowian approach – a metamodern method that shapes the thinking patterns of those who apply it?”. Meanwhile I changed my thinking and as a consequence this talk is about why the title is wrong.

To keep this paper brief I will not talk about metamodernism, a concept Judith Aston linked to i-docs (Aston 2022). For more details on how I think Metamodernism is related to korsakowian practice please check out the talk I gave at the Mobile Studies Congress in December 2023.

Today I will talk about multiperspectivity and its counterpart monoperspectivity and thereby I hope to illuminate the understanding of what korsakowian practice is and what it is good for.

How I got to where I am

I am the guy who invented Korsakow, a software system that is commonly thought of as a tool to create interactive documentary. Korsakow came into being in 2000 and since then it became the center of my life and my thinking.

For the first 15 years my energy mostly went into producing Korsakow projects (Korsakow films, Korsakow Installations, Korsakow Shows). After that I moved my focus more towards reflecting and trying to understand what I vaguely described as “the magic of Korsakow”. My turn towards research was inspired by people like Matt Soar, Judith Aston, Adrian Miles and others who I had the privilege to get to know personally, not so much through their writing as I did not have the necessary academic language skills. For many years I did my private research, in a style that Michael Hohl, who is now one of my PhD supervisors, calls *cowboy research*.

Two and a half years ago I was granted the opportunity to quit my day-job and fully focus on my research. I am currently doing a practice based PhD, and in this presentation I want to report where I am currently at.

My autoethnographic research

After spending quite a bit of time, wrestling with the system and trying to learn academic languaging, I turned towards auto-ethnography with a focus on my first works, which includes the reconstruction of my very first computer based narrative work called Small World which I made in 1997, the piece with which the whole story started and that later led to Korsakow. Small World could be described as a nonlinear, interactive slideshow and is in many ways the predecessor of Korsakow, the software tool that still is being used today. Small World, puts flashlights on 54 data points of what it is like to grow up in a small town or and more concretely what I experienced growing up in a small town in Bavaria. Back then, I built a small world in Macromedia Director, a software that later became Adobe Director and which later went the way of all earthly things and largely disappeared into obsolescence.

I am currently in the process of reconstructing Small World in Korsakow.

The thesis with which I started my PhD, and which is also reflected in the title of this talk, is that my particular way of working with korsakow – which I call korsakowian – has shaped my thinking in a way for which I have been using the term “multi-perspectival” since 2012 (explained here).

What do I mean by multi-perspectival?

Being multi-perspectival is the habit, one could also say the pleasure or compulsion, of looking at, considering and understanding things from as many perspectives as possible. It is a particular pleasure for someone who is multi-perspectival to hold contradictory or even mutually exclusive perspectives in the head at the same time. It’s like juggling and the more balls you can keep in the air, the greater the pleasure. On the other hand, there is the mono-perspective, which assumes that there is one best perspective from which to understand the world and strives to find this perspective. People with a multi-perspectival disposition are characterized by the fact that they are always delighted when someone comes along with a clever thought that renders their own system of thought obsolete or at least reveals a perspective that makes them say, “Oh, I never thought of it that way”. There can never be such a thing as truth for someone who is multi-perspectival, as all perspectives can never be considered. Mono-perspectival people strive to find the *best* perspective and once this perspective has been identified, they tend to propagate and defend it. Mono-perspectival people generally feel little pleasure when their ideas are criticized and viewed from a different perspective that contradicts their own. Multi-perspectival people, on the other hand, are often extremely skeptical when one perspective is presented to them as an unquestionable truth.

This is, of course, a very and possibly overly simplistic depiction. Of course, no binary distinction can be made and it would be a little ridiculous to divide humanity into mono-perspectival and multi-perspectival people, so one should rather imagine a scale with mono-perspectival on one side and multi-perspectival on the other. Individuals then tend to lean in one direction or the other. People are often topic-dependent, mono- or multi-perspectival. Experts tend to develop a more multi-perspectival view in the field of their expertise, which means they see things in a differentiated way and usually don’t take a single viewpoint. However, the multi-perspectival view in one subject area does not prevent mono-perspectival experts from not transferring the realization that things are complex and ambiguous to other areas.

There is no value judgment associated with mono- or multi-perspective. Both have advantages and disadvantages, I went into this in my talk at the I-docs Symposium, Crisis and Multi-perspective Thinking in May 2022. The talk is documented on my blog.

Tool affects thinking vs. tool attracts thinking

Korsakowian practice affects thinking and sense making (Aston 2022; Wiehl and Lebow 2016; Soar 2014; Gaudenzi 2013), in the sense that it questions linear causal thinking, calls categories into question, and directs attention instead to circularly acting relations within complex systems.

So far I have assumed that my style of working with Korsakow – the korsakowian approach, which I would describe as an extremely open approach to any topic – that this korsakowian exercise was formative for my multi-perspectival thinking.

This is how I have perceived it so far – that the korsakowian approach has reinforced my multiperspectivity. My auto ethnographic research now suggests something else, which my mother would simply describe as: I have always been like that. This in turn would suggest that it is not so much the medium and the way of using that particular medium that makes the thinking, but rather that a medium allows, or makes possible, a certain way of thinking that is already inherent in the individual. In general terms: certain forms of media attract certain kinds of thinkers, in specific terms media that affords a korsakowian approach attracts multi-perspectival thinkers.

This is also suggested by a series of intensive conversations I have had with other practitioners in the field of interactive documentary. In this context, the dust has fallen from my eyes: I have never succeeded in convincing anyone of the korsakowian approach who has not already practiced multi-perspectival thinking.

Conversely, it can also be said that no one has ever succeeded in teaching me a mono-perspectival way of thinking.

5. Conclusion

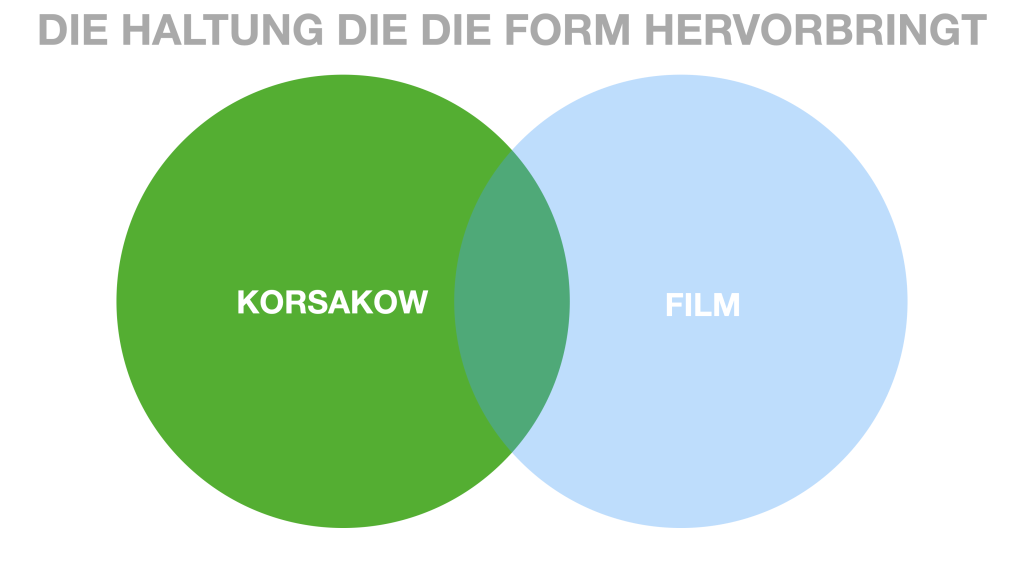

Korsakow is a tool that affords a multiperspectival (korsakowian) approach but it can also be used in a more mono-perspectival way. This is because the mono-perspective is always part of the multi-perspective (it is just one of many perspectives). So Korsakow is not multi-perspectival per se, but it does afford a more multi-perspectival approach than more linear legacy media can. The same applies to other potentially korsakowian media, such as YouTube, Twitter or podcasts. This is confusing in that at least podcasts are neither interactive nor non-linear. The commonality is the digital and I would like to speculate at this point that it might be especially the abundance of resources that allows us to not have to know in advance the outcome of a media production, and that makes the korsakowian approach possible on a large scale. Interactivity might be overrated, one could say.

On the basis of this speculation, I would like to continue my research.

So the title for this talk should have been:“The Korsakowian Approach – A Metamodern Method That ShapesHelps The Thinking Patterns Of Those Who Apply It?”