There are no wrong decisions and there are no right decisions.

Decisions are taken in small fractions – too small to be relevant.

When you zoom in to a moment in time, where a particular decision is taken, there are always decisions before that moment. Earlier decisions, that led to the moment when this decision was possible, and before that were lots of other moments, when small decisions were taken. Lots of micro-decision so to say. And every micro-decision had alternatives. When was the exact moment, when George W Bush decided to go to war against Iraq? For sure not when he went down the aisle in the White House towards the podium, where the cameras were waiting. So when did he take that decision? You could go back in time further and further, maybe “the real” decision was taken by someone before Bush. Whatever moment you would want to identify, there were decisions taken before that, that were necessary to create a world in which the next decision was in the space of possibilities.

But we agree, there was a decision to go to war. But what we mean with “decision” is basically a cluster of micro-decisions, stretched over a longer or shorter period of time.

Why is this important?

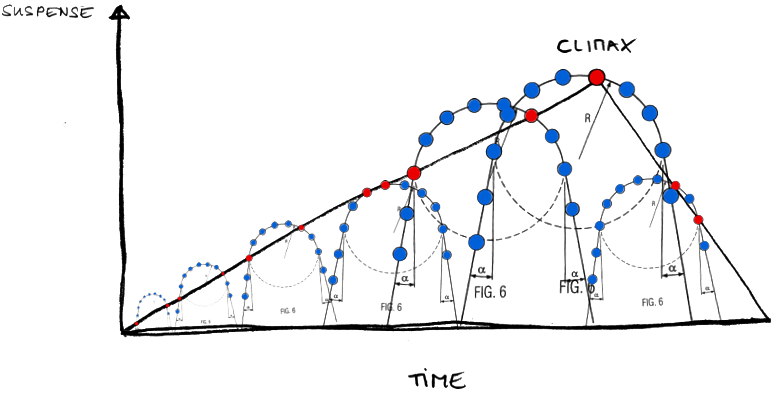

We speak of a decision and we are used to conceptually nail it down to a point on a timeline. The logic of the timeline (in this talk I called it “Hollywood logic”) suggests that a decision, once taken, can not be changed (because it is in the past). But if you think of paths instead of decision-points – you can always adjust a path, even without leaving it, as the path is created while you are moving. Even after Bush declared the war, he could have changed the path at any point in time, after he has observed that the direction taken, leads into misery.

But the audience (trained in Hollywood thinking) does not appreciate politicians changing their mind once they made “a decision”. Because of that politicians feel like they have to stick to their decisions. Politicians seem to spend a lot of energy on ignoring observations, because they don’t want to look like they took a wrong decision.

In a world, where the concept of a decision does not exist, you can not take a wrong decision. You can easily adjust your path when you feel you are getting into hot waters. That goes for politicians and of course for everyone else. As observation shows, the weird concept of decision-points on a timeline – with each decision with potentially scary consequences – makes it had to adjust paths, leads to bad results and makes people miserable.

The simple way out: Look at it like that: Every moment holds many possibilities – whatever decisions you took in the past.